STEFANO RIELA

Europe Institute, University of Auckland, New Zealand

It is undoubtful the role that the United States (U.S.) played and is still playing in shaping the integration process on the other side of the Atlantic: the creation of the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation to manage Marshall Plan aids; the push towards the Economic and Monetary Union after the collapse of Bretton Woods agreement on quasi-fixed exchange rates; the renewed interest for a permanent structured cooperation in security and defence policy (PESCO) after a President-elect’s tweet questioning the usefulness of NATO.

A recent proposal by Biden’s Presidency shook the almost decade-long impasse on international tax coordination and revamped the debate about tax policies within the European Union (EU).

In an economic framework dominated by global value chains, some countries built their comparative advantage on the physiological incompleteness and (in) voluntary imperfection of tax rules and offer attractive tax conditions to multinationals.

Complex operations and corporate constructions are necessary to turn evasive tax strategies into elusive ones, the costs of which make them convenient only for large companies. Tax havens have nothing heavenly both for small and medium-sized enterprises and for high-tax countries; for the former, they are responsible of an unfair regressive taxation, for the latter, they subtract valuable tax base. This “race to the bottom” amounted to $ 427 billion in tax avoidance and evasion last year (Tax Justice Network) and reduced much needed public investment (Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen).

For the principle of communicating vessels, countries with low taxation and consequently with fewer resources, offer a lower level of public services, forcing the companies located there to bear higher private costs. This public-private neutrality that would have reduced the benefit of locating one’s business in tax havens has been jeopardized by the growth in exports of intangible assets, eg, patents, from high-tax countries and in export of digital services, eg, online advertising, from low-tax countries.

For this reason, since 2012, the OECD and G20 countries have been trying to find a solution to combat the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). Despite an agreement on general principles (the importance of transparency and of harmless tax competition), the results of this coordination have not been significant so far as taxation remains a firm cornerstone of national sovereignty characterizing the socioeconomic model of a country.

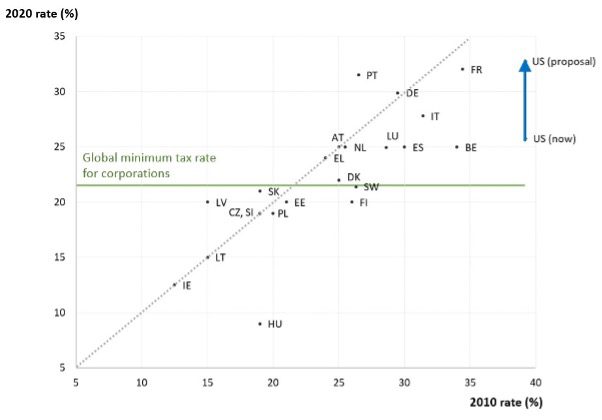

Combined corporate income tax rates[1] in EU and OECD countries and in the U.S.

Source: OECD

The core of the U.S.’ proposal is twofold: a) adopting a minimum tax rate of 21% on global profits; b) allowing countries to tax large multinationals based on sales in each country.

The first proposal came along with announcement of a tax rate increase on profits to 28%; this to help finance an investment plan estimated at 2 trillion dollars. The new rate would be midway between 35%, which characterized almost the entire post-World War II period, and 21%, adopted by Trump’s Presidency in 2017.

The tax rate on income classified as ‘Global intangible low-taxed income’ (GILTI) would double from 10.5% to 21% and the tax would be assessed country by country and not in an aggregate manner. For US companies, the deduction for profits earned abroad thanks to intellectual property would also be eliminated. So, if an American firm pays less than 21% to a foreign government, it will have to pay the difference to the U.S. administration regardless of where it claims to have made the profits. This should discourage, ceteris paribus, the shift of profits away from the U.S. when the combined rate will reach almost 33%: still below 39% pre-Trump, but the highest in the OECD according to the 2020 data (the combined rates in Australia and New Zealand are respectively 30% and 28%).

With the second proposal by Biden’s Presidency, large corporations would pay taxes where sales are made and not where profits are shifted. Finally, it will be possible, for every country, to tax the web giants without risking any U.S. retaliatory tariffs as announced by President Trump for ad-hoc taxation proposed by France, the UK and Italy. The American proposal would cover all sectors, thus shifting discrimination from a vertical dimension (the taxation proposed only for the digital sector) to a fairer horizontal one (only large companies).

The EU has no explicit legislative competences in the area of direct taxation but the TFEU (art. 115) authorises the Union to adopt directives on the approximation of laws, regulations or administrative provisions of the Member States which directly affect the internal market; adoption requires unanimity in the Council and the consultation procedure.

Proposals to harmonise corporate tax have been under discussion for several decades as demonstrated by the list of reports in this sector: Neumark (1962), Van den Tempel (1975), Ruding (1992) and Bolkestein (2001). Due to insufficient results, the last report moved its harmonization target from tax rate to tax base. In 2011 the Commission proposed a ‘Common consolidated corporate tax base’ (CCCTB) to facilitate the business of cross-border firms while leaving untouched the sovereignty of Member

States in setting their own rates of corporate tax. The proposal has not been approved yet and Member States have confirmed their uncoordinated approach: today, tax rates range from 9% in Hungary to 32% in France (see OECD data in the figure above).

What’s next?

This recent proposal by Biden’s Presidency may find a mixed majority of both Democrats and Republicans who are no longer be willing to sacrifice, on the altar of capitalism, fiscal resources after having sacrificed employment already flown to lowcost countries.

Even if the rationale behind the U.S. proposal is domestic (ie, to facilitate the recovery after Covid-19 especially in times of booming public debt), there are positive international effects: an invitation to multilateralism is welcome for the transatlantic dialogue after four years of monologues.

However, it is important to avoid overshooting on corporate taxation as the additional tax burden may be passed on to consumers, workers and shareholders on the basis of different elasticities and different bargaining powers. Hence, with the aim of curbing one type of regressive effect (ie, big firms pay relatively less taxes than small firms) another type may arise (eg, workers that are more substitutable than others can experience a reduction of their salaries).

[1] This rate shows the basic combined central and sub-central (statutory) corporate income tax rate given by the central government rate (less deductions for sub-national taxes) plus the sub-central rate.

Bio: Stefano is a lecturer of economics of the EU at Bocconi University, University of Auckland, and lecturer of competition policy at ISPI (Italy). He worked on many academic projects, eg, with the Allianz Kulturstiftung (Germany) and Babson College (USA). He was economic advisor at the Communications Regulatory Authority in Italy, research director at ResPublica Foundation, and consultant of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs during the Italian Presidency of the Council of the EU.